My Protesting Shoes

My Protesting Shoes

Fatima Hassani

Summary:

In a queue at the border, a young woman stresses over her choice of clothing, especially the white shoes she is wearing. These white shoes could ruin her chances to cross safely. But then she realizes the shoes have something to say.

Story:

Early morning of October 12, 2021. After passing a lot of Taliban checkpoints, we arrived at the Torkham border between Afghanistan and Pakistan. To avoid attracting attention, we divided into groups of ten.

What followed were the most stressful six hours of my life. It was the first time I had ever stood so close to a Taliban soldier. The things that made them frightening were their appearance and, of course, their guns with the two chains of bullets looped over their chests. The queueing area was separated by a grating. On the right side stood the women, and on the left side, the men. There was a narrow space in the middle where the Taliban soldiers patrolled. I’d always wondered how they felt about the terrible things they did, so I snuck a look in their faces, but I saw no feeling: no anger, no fear, no happiness, and no worry.

The queue was moving like a paralyzed turtle. I struggled with my clothes all the time to make sure my hair did not show and that my body was absolutely covered to hide my identity, although I wore a dark green dress that came to my ankles and a big black scarf with a black mask. The worrying point was my white fabric sneakers.

The Taliban’s flag is white, so they believe that wearing white shoes and socks is disrespectful. I wore them to demonstrate my dissatisfaction with their system, but as soon as I was in line, I wished I hadn’t. The weather was only warm, but it seemed hot with those clothes and so much stress.

My heart broke when I saw children with blue backpacks bearing the UNICEF logo trying to hide among trucks that were crossing into Pakistan. The children would slip under the trucks and walk at the same speed, hoping not to be noticed. But it seemed their trick was familiar to the Pakistani soldiers. Still, they tried several times in the hopes of succeeding. They were just a bunch of schoolkids with eager eyes trying to leave in their dirty clothes. Those enormous truck tires are still in my nightmares.

“Hey, you!” shouted a Taliban militant when he saw me.

I felt my heart stop. With shaky legs, I turned to face a tall man with kohl eyes, an unkempt beard, and a gun on his shoulder. When I opened my mouth to say something, he interrupted me.

“Where is your man?”

According to the Taliban’s rules, women can’t travel more than seventy-two kilometres without a male family member. I was travelling with Mr. Joybari, one of the teachers of Marefat School. He came over to speak with the Taliban soldier. Although it was painful that the soldier didn’t even consider me worthy enough to speak to, I was happy not to have to answer his questions.

As I got near the gate, my stress level got higher and higher. I knew that when I walked on Pakistani soil for the first time, I’d feel like I’d dropped a heavy dumbbell after carrying it for a long time. But I was not happy because I had left behind my family, friends, country, and the culture and beliefs that I had grown up with. I felt like an isolated bird cut off from the rest of the flock.

There were so many things that I wasn’t allowed to say as an Afghan girl, but my shoes could say them. I grabbed my long skirt. Lifting it, I walked through to brightness with those white sneakers protesting with every step.

Fatima Hassani was born in Ghazni, Afghanistan in 2001. She graduated from high school in 2018 and started in the Business Administration field at Chandigarh University in India on scholarship in 2020. She was home visiting in Afghanistan when the Taliban took the country. On 12th of October, 2021, she entered Pakistan and since then has been waiting for a visa for Canada.

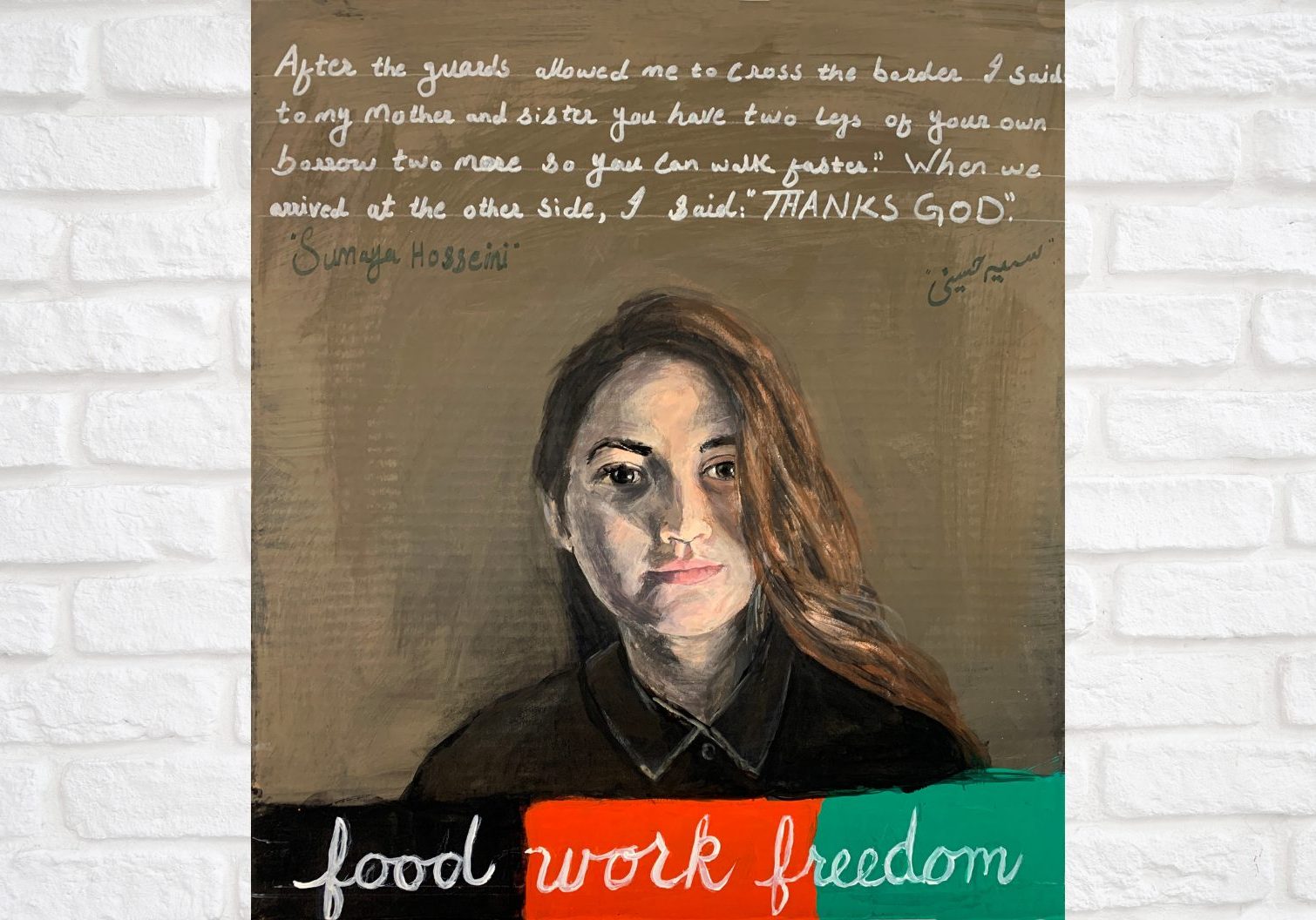

Portrait: Linda Duvall with Fatima Hassani

A Bird Cut off from the Flock

Oil pastel and chalk pastel on paper

2023

“Fatima and I started off by just meeting and talking. One thing that Fatima talked about a lot was what it felt like to be away from her family. She talked about feeling like a bird cut off from her flock. We talked about who her flock was – her siblings, her parents, her grandmother, her aunts and uncles, so many more.

The next week we looked on the computer for images of birds. Rather that working with specific kinds of birds, we chose a generic looking one, and printed it out in various smaller sizes. Then Fatima started to colour them.

The first bird, coloured with oil pastel, was very bright and present, clearly the Fatima bird. Then we cut out the birds in various smaller sizes. Fatima coloured them using chalk pastel so the colour was softer and less defined – all of her absent flock. Fatima worked with the chalk pastel with her fingers, smudging and smoothing each bird.

The birds were arranged on a wall so that the bright Fatima bird was some distance from all the other birds.”