My Brother’s Finger

My Brother’s Finger

Marzia Naderi

Summary:

An ordinary Afghan truck driver exercises his democratic right to vote. Under the Taliban, this effort endangers his life and well-being.

Story:

Mohammad Hussain, my brother, was working with his dump truck. Over the last three years, the market for that type of work had declined in Kabul. He had been forced to drive to districts outside the city, including our village on the other side of the Maidan Valley. It was also known as Death Valley because the Taliban ambushed people there.

On the day of the 2014 presidential election, Hussain planned to vote. After voting, his finger would be inked. Because of this, my mother was concerned about the Taliban, but my brother reassured her they mostly targeted Afghan army personnel, government officials, and individuals who collaborated with foreigners. He added, “The colour will go away quickly, just like the first round of the election. But I will tell the poll station staff not to ink my finger.” But later that day, he returned with a blue finger.

Two days after the election, Hussain decided to go to our village to sell some firewood. My mother said to him, “It is not essential. You can travel in two or three days.” But my brother replied, “It’s not a big issue! I’m an ordinary driver with no risky background, and I’ve never been harmed by the Taliban.”

The next day, as usual, I poured water on the ground for my brother. According to our beliefs, water is a resource of life and a symbol of purity, considered sacred by the ancients. Travelling then was not as easy as it is today. It was full of danger and treated as a kind of death and rebirth: pour water and trust that it will protect the passenger. I was confident that he would be in good health when he returned home.

Hussain left before sunrise. There was no cell phone reception on the way, so we had to wait until he arrived late in the afternoon to call him. But at approximately midday, my father received a call from Watan hospital. My father, uncle, and cousin rushed there. The rest of us were left behind, crying. We didn’t know what had happened.

My mother said, “I can’t wait any longer. I am going to go see what happened to my son with my own eyes.” So, my mother, aunt, and I left the house. I just put on the first pair of shoes by the door, brown sandals. I couldn’t run in them because they hurt my toes.

When we arrived at the hospital, I saw my father in distress. My uncle said, “Hussain’s finger was cut off by the Taliban.”

My mother collapsed. My aunt clutched her head. I was too shocked to express my emotions and just stood there like a statue. I could hear my brother screaming in pain. Suddenly, I felt nauseated and started crying. My uncle brought us home.

Late at night, they returned home with Hussain. I stared at his pale face and parched lips. His restless eyes revealed the extent of his suffering. His sky-blue Afghan clothing, which had been spotless before, was now covered with blood. In that blood, I saw how a person’s ideas and beliefs might lead him to be hateful, vicious, and frightening. I hated the Taliban even more.

A few days later, Hussain told us how the Taliban had stopped his car and discovered his inked finger. Two of them held down his hands and head while the other cut off his finger with a sharp knife. He said, “I blacked out when my finger was chopped off.” I could sense fear in his words and eyes.

After that black day, I never wore those sandals again. In fact, I don’t recall ever wearing sandals since then.

Marzia Naderi is from Afghanistan. She graduated from Kabul University with a bachelor’s degree in science. She moved to Pakistan with her husband and two and a half-year-old child after the Taliban took over the country. They wish to travel to Canada in order to live as a free people.

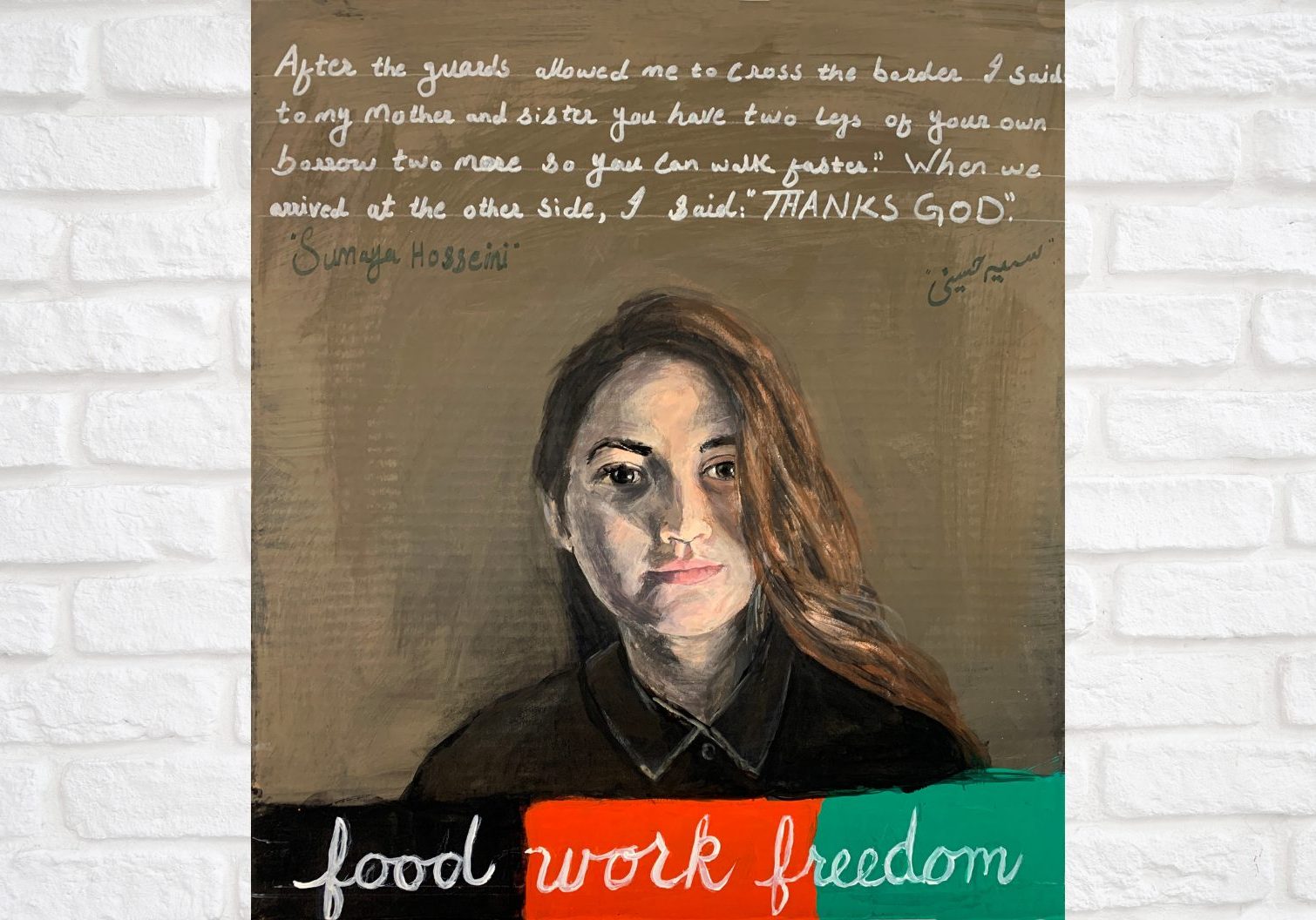

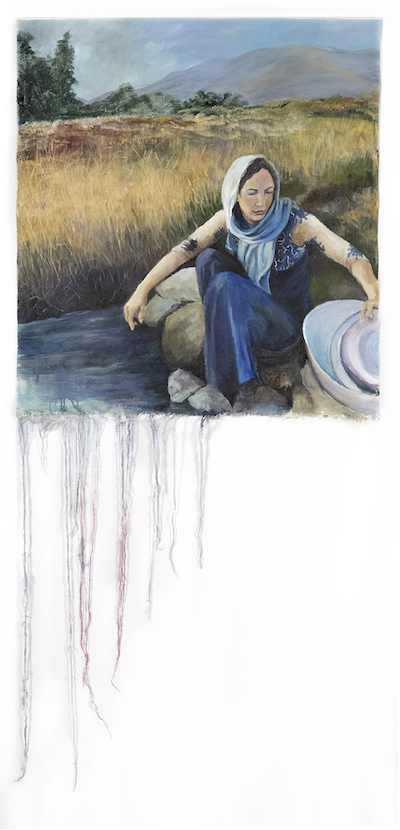

Portrait: Elizabeth Babyn with Marzia Naderi

Marzia by the Water

Acrylic on canvas, torn gauze strands

2023

Size: 41″ x 77″